Bishkek sits in the heart of Central Asia, surrounded by natural beauty. SRAS programs in Bishkek offer two categories of travel components. All regular programs offer several trips to see more of Kyrgyzstan, particularly its rural cultures. Students specifically on SRAS’s Central Asian Studies program have an extended travel component that covers multiple Central Asian countries and immerses them in the diverse histories, cultures, and societies of Central Asia. Students not on the Central Asian Studies program can often take some of these trips as optional add-ons. The following are a sampling of reviews from the extended travel component. Note that trips and intineraries may change and not all trips may be offered all semesters.

All Programs: Travel Kyrgyzstan

All regular programs offer multiple short trips out of the city.

Burana Tower: Legend and Nature

By Matthew Hickey (Spring, 2022)

Endless waves of rolling hills as far as the eyes can see, livestock unrestrained by fences roaming freely, and imposing mountains looming over it all. This was what we experienced on our marshrutka ride to Burana Tower on an SRAS/London School arranged cultural outing.

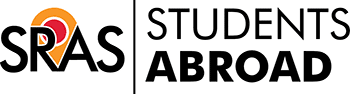

Once there, our guide gave us the history of place. The Burana Tower was built in the 11th century as a minaret, which are used in Islam to call the faithful to prayer. It was built under the Karakhanid Empire and is part of the last remains of the ancient city of Balasgun. The city was abandoned after a Mongol sacking followed by an outbreak of the Black Death in the mid-1300s.

Burana Tower is around 30 meters tall but it was said to have been 45 before parts of it collapsed over the course of several earthquakes. Next to the tower lie various grave markers from the 6th century, you can still make out the smiling faces clutching wine cups despite the hundreds of years of erosion and decay.

The legend of the tower’s creation is both new and familiar. It tells the tale of a mighty khan who had a daughter; he celebrated this occasion with a massive feast; to this feast, he invited various soothsayers and wise men to tell the fortune of his newborn daughter. A single soothsayer came forward and declared that the daughter would die from the bite of a black spider by her 16th birthday. Out of fear, he built a stone and brick tower to protect his daughter, she was forbidden from leaving, and only servants could enter. Each servant inspected the items to ensure no spiders could enter. Each servant kept a vigilant watch over the tower to protect the khan’s daughter. Each servant knew the prophecy and the risk.

Upon her 16th birthday, the Khan was pleased, his daughter had survived and thrived in the tower. In celebration of this momentous day, he picked a bunch of grapes and brought them to the tower for his daughter. He failed to notice the black spider hiding in the grapes in his joy. The spider bit the hand of the daughter, killing her right in front of the Khan. His wailing is said to have torn apart the tower’s roof sending rocks flying below.

Today, standing atop the tower, looking out over Kyrgyzstan’s vast planes can easily conjure images of herds of horses and nomads crossing. The view allows one to truly appreciate the beauty of the region and puts in to perspective how important it is to protect its nature and history.

This locale is home not only to the history of Kyrgyzstan but the future as well. Beneath layers of earth lie the foundations of an ancient palace waiting to be uncovered. The funds to unearth this beautiful link to the past have not yet been allocated but one day we shall hopefully see what wonders the Karakhanids built here.

There were various artifacts uncovered from the region on display from rings and jewelry to weapons and art. A yurt sold Kyrgyz souvenirs and ice cream, a treat which was highly appreciated in the blazing sun. Horses and cows grazed peacefully nearby as stray dogs wandered amicable about.

Afterwards we headed to the natural hot springs of Issyk Ata where we hiked a small portion of a mountain in order to enjoy the breathtaking view. A friend commented that no matter where we looked it seemed as if we were stuck in a Windows screensaver. The views were so breathtaking I do not think I will ever get used to them.

Overall, the day was an excellent introduction to Kyrgyzstan’s history and nature.

Talas: Ancient and Rural Tradition

By Kathryn Watt (Summer, 2019)

Talas is a small town in the countryside of Kyrgyzstan, situated in a rural, mountainous region. For the opportunity to meet locals and learn about Kyrgyz folklore, this trip is ideal. The London School and SRAS organized a weekend trip for us.

They took care of everything – transfer, packed lunches on the road, home-stay, and excursions. As a result, the trip was very stress free. They even notified my home-stay of my dietary requirements and ensured that there was vegan food available to me.

It was early evening when we arrived at a small village near Talas, after 5 hours of winding round beautiful mountain paths and through ramshackle villages. The road was bumpy and the roadside toilets questionable, but the views made it more than worth it. We entered our home-stay through a courtyard, took off our shoes, and were immediately seated round a spread of fruit, bread, jams, and tea, while we waited for a local musician to arrive. The musician was known as a Manaschi, an honored storyteller of the local community. He played traditional instruments and sang traditional songs (with the exception of an outburst of “despacito”). It was a combination of the traditional and the modern, a young man dressed in western clothes, wearing a Kyrgyz hat and singing his heritage. After a dinner of potato manti, we went for a walk in the surrounding countryside. Cherry blossom trees framed a landscape of snow capped mountains, babbling brooks, and fields stretching for miles – it was truly a sight to behold. It was wonderful to breathe the fresh air and look up to see a multitude of stars, shining through the black canvas of the sky.

My room was modestly furnished but tastefully decorated, both the floors and walls carpeted in traditional Kyrgyz style. In one corner colorful mats were stacked high upon a metal chest and in another corner, a bed was made up on the floor. The spring climate in Talas is colder than in Bishkek, but I was provided with a small electric heater to keep warm. I spent the evening talking to my host sister, before taking an early night and going to bed.

The next morning, I woke to blazing sunshine and a breakfast of buckwheat, potato, and carrot (specially prepared for me as a vegetarian), washed down with a glass of compote. By 9:30am, we were on the road again, headed to the Manas Ordo Complex, a park dedicated to Kyrgyzstan’s national hero, Manas. He was a great warrior of old, whose story is traditionally told by Manaschis. The story of Manas has only been written down in recent years, as the art of Manaschi is an oral tradition, passed down from generation to generation for hundreds of years.

First, we climbed an old looking post, to get a view of the complex. On one side, we could see a pitch for Buzkashi (a Central Asian rugby-like game played on horses, with a goat carcass for the ball), and an old graveyard, featuring impressive tombs. We also saw the alleged tomb of Manas, an ancient feature with engraved walls. Next, we had a tour in the museum. The exhibition depicted the life of Manas and the Manaschi through art, figurines, and traditional artifacts such as clothes and weapons. Then, sitting in the sunshine under a canopy of trees, we witnessed another manaschi performance, to hear the epic stories of old.

This was one of my favorite London School organized trips, though the journey was very long for such a short visit, so I would have preferred to stay an extra day. I would recommend this trip to anyone who enjoys nature, world music, authentic cuisine, and cultural experiences.

Horse Trek: A Glimpse into Nomadism

By Daphne Letherer

This material is also featured on Folkways, which is part of the SRAS Family of Sites. See it and other reviews and information about Kyrgyz horse treks here.

The sun shone, happy in the sky. The roads were no longer dirt, but mud, and they felt like rumble strips. It was worth it, though, once we were in the mountains. We stopped in a village in the valley, where we were split up between cars which toted us up the mountain. There, we mounted our horses. Many of us had trouble getting our horses to obey our commands, and we ended up circling around for a long time, trying to master our horsemanship with the assistance of two trained guides.

We were not told the horses’ names, but I called mine Alejandro. He wasn’t the most amicable horse. Going up the mountain, he was extremely slow. Eventually, one of the guides gave me a whip, and that sped him up, temporarily. The mountainside was beautiful. Initially, I was trying to steer Alejandro away from rocks and dips in the ground, but then I remembered that horses aren’t cars. He knew where he wanted to go. I think our relationship slightly improved after that. We reached the top, where we ate lunch amidst a herd of cows and fog. There was a giant rock on a lip of the mountain, which quickly attracted many of the students. This was the perfect spot to see the valley below, the slopes of the neighboring mountains, and Issyk-Kul nestled in the distance. After climbing all over the rock and taking pictures, we made our way back to the horses.

The ride down was certainly more stressful than the ride up. Alejandro slipped at one point, causing my leg to fly out of the stirrup and causing me terror. Then, he decided to get off the path and climb up on the ridge next to it, heading back up the mountain instead of down (to be fair, he wasn’t the only horse who did that). There was a point that I think Alejandro just wanted to get home, because next thing I knew, we were at the front of the pack for the first time. He would begin trotting down, following an ill-behaved horse that kicked the others, switching back before the rest of the group and leaving me very confused on as to where I should be. We returned to the farm, and Alejandro wasted no time in finding his place along the fence.

After dismounting, we were split into two groups. One was invited to the family’s yurt. There, we learned about their decorations and everyday life. The other looked at and pet their foals, which were tied up not far from the yurt. After the groups switched and experienced what the other had, we built a yurt. Well, saying we built a yurt is a little generous. Mostly, we watched the experts (consisting of our guide from the London School, a horse guide, and the young couple to whom the yurt belonged) build a yurt, occasionally stepping in to tie something. First they stood a fence-like frame. Then we all held poles to make the roof and placed yarn decorations on the interior. They placed the swaths of felt on the roof and sides, and ta-da! The yurt was built. I can’t tell you any specifics about the process, because nothing was said about it. All I know is that it was a smaller yurt, for when members of the family travelled. As we stood around the yurt, we were taken over by sheep, which were quickly shooed away. I was amazed by the beauty of the landscape. The horses, sheep, and dwellings of the family who lived there were extremely picturesque with the mountains as their backdrops. Behind green mountains there loomed massive mountains coated in rock and snow, a haze from the distance wrapped around them.

I was certainly spoiled to spend a weekend in the stunning mountains of Kyrgyzstan, by Lake Issyk Kul, during my first days in the country. I’m glad I was able to go on the excursion. Even though I was exhausted, it was beautiful, and it set the tone for my stay here in Kyrgyzstan. I learned about some culture and history, food and environment, before moving into a dorm room and starting to attend class. Now that I’m busy with classes, I certainly appreciate any trips into nature, even if it’s a park in the city. Issyk Kul is a beautiful place that has yet to be developed. If it were a place in the States, surely there would be condos, lake houses, shopping centers, and tourist traps all around. Hiking around Issyk Kul gave me exactly the experience I wanted when I signed up to study Russian in Bishkek and gave me a wonderful introduction to living in Kyrgyzstan.

Issyk Kul: Kyrgyz Family Vacations

by Mikaela Peters (Summer, 2019)

At the end of August, the water in Lake Issyk Kul is refreshing and not overly cold. Similar to the way that American families may go to Florida every summer for vacation, Issyk Kul is a vacation spot of choice for many Kyrgyzstan natives, especially those living in the capital, where it can become absurdly hot in the summer. Because Issyk Kul has been receiving an influx of foreigners, average prices to vacation in the region are rising. This has made it a little more difficult for local Kyrgyz families to continue their annual vacations to Issyk Kul.

Issyk Kul means “warm lake” in Kyrgyz. While surrounded by the snow-capped Tian Shan mountains, the lake never freezes due to its depth, salt content, and the fact that water from local hot springs feed into it. It is the seventh deepest lake in the world. About 118 rivers and streams flow into it. At Lake Issyk Kul, there is a lake, known as the Dead Lake, or Tuk Zol, a salt water lake formed from a decrease in water level from Issyk Kul. It is believed by locals to cure all sorts of skin-related ailments through use of the mud from the lake. The Dead Lake is located 300 meters from Lake Issyk Kul, and is accessible through the village of Kyzyl Tuu.

Lake Issyk Kul has long been a centerpiece of local culture and has folktales surrounding it that date back to pre-Islamic times. For example, there is a myth about its formation that says that it started with a local king who had donkey ears. Whenever he would go to get his hair cut, he would have to remove his hat and reveal them to his barber. He threated to killed his barbers if any of them revealed his secret. One barber, unable to contain the explosive secret within himself, yelled the secret into a well, but he didn’t cover the well afterwards. The secret caused the well water to rise and it flooded the kingdom. Today, the ruins of the kingdom lie under the waters of Issyk Kul.

During the time of Soviet Union, the Soviets favored the north shore of the lake, which lead to industrialization of some areas. This created economic prosperity on the north shore, but discouraged traditional Kyrgyz culture there. The south shore remained more rural and traditional. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the southern shore became a cultural attraction, having held onto its nomadic cultural heritage.

Today, numerous guesthouses throughout the region serve the tourists who now come to the area for hiking and to view the area’s natural beauty and unique geological formations. Some of these include the Skazka (Fairy Tale) Canyon and the lush, green Barskoon Waterfalls, both of which our group had the opportunity to see.

Arranging a trip to Issyk Kul is worth the effort. Marshrutkas leave for the south shore from Bishkek numerous times a day via Bishkek’s bus station. In addition, travel groups organize these types of excursions, too. Regardless of whether you go to Issyk Kul on a program, with a tour group, or on your own, it is not a natural wonder you want to miss out on.

Ata-Beyit: Reverence for the Oppressed

By Sophia Rehm (Fall, 2014)

This material is also featured on Museum Studies Abroad, which is part of the SRAS Family of Sites. See it, with many other pictures of the excursion here.

Ата-бейит (Ata-Beyit, Kyrgyz for “Grave of Our Fathers”) is a memorial complex located in Chong-Tash, a village and skiing destination in the Chui Province about 15 miles south of Bishkek. The site honors two dark episodes in Kyrgyzstan’s history: mass murders that occurred in 1938 at the hands of the NKVD during Stalin’s purges, and the deaths of the revolutionaries who fought in the nation’s 2010 Revolution. Powerful sculptures and monuments pay tribute to those who died in the two conflicts, and a modest museum, shaped like a yurt, covers the political climate in Kyrgyzstan in the 1920s and 1930s, and the Stalin-era repressions.

In 1991, the daughter of a former NKVD officer came forward with a secret her father had told her just before his death. He had witnessed a mass execution at the hands of the NKVD, and this tip eventually led to the discovery of a mass grave in Chong-Tash. In 1938, NKVD officers took 137 (possibly 138) people – members of the intelligentsia including ministers and scientists, and representing 20 nationalities – from a prison in the capital to Chong-Tash, where the prisoners were shot and secretly buried in an underground kiln once used for making bricks.

After their discovery, the remains of the victims were exhumed and moved to a formal, shared grave about 100 meters away. This grave, in the center of a square beside the museum, lies beneath a horizontal sculpture of a тундук (“tunduk”) – the crucial circular piece at the apex of a yurt. The sculpture rests on a large, stone platform, the sides of which are inscribed with all the victims’ names. Stone reliefs along the stairway down to the square from the road above depict suffering at the hands of uniformed men. The kiln where the remains were found can be viewed across the road from Ata-Beyit, behind a glass partition.

The 1938 execution is the largest known to have occurred in Kyrgyzstan during Stalin’s anti-nationalist purges. One of the men killed in Chong-Tash was Torokul Aitmatov, a politician and father of Chinghiz Aitmatov, a writer and diplomat who is Kyrgyzstan’s most famous literary figure. Chinghiz Aitmatov helped found the cemetery in Chong-Tash, and after his death in 2008, he was buried there as well. His remains lie beneath a memorial of their own, in front of a white stone gate along the far edge of the square. One side of the gate is inscribed with a quote of Aitmatov’s: “Самое трудное для человека – быть каждый день человеком” (“The most difficult thing for a person to do is to be a person every day”). The other side features a portrait of the writer. In the middle, an archway frames a sculpture honoring Aitmatov’s novel, Jamila, and a view towards the village, fields, and mountains beyond.

The revolutionaries honored here also have a history of their own. In 2010, Kyrgyzstan experienced its second Revolution in its decade of independence from the Soviet Union. On April 6 and 7, thousands of protesters filled Ala-Too Square and stormed the White House in Bishkek, reacting to economic hardship and government corruption. Battles with police culminated in bullets fired at the crowd, and over 40 protesters were killed. The protests ousted President Kurmanbek Bakiyev (though the Revolution continued, with escalating violence between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks). Most of the victims of the April protests were buried at Ata-Beyit, down the hill from the museum and the square in a graveyard of their own. They lie beneath individual granite stones inscribed with the names and images of the (mostly young) men. A wall beside the graves lists the names of all who were killed.

Ata-Beyit is not a popular destination for locals. Many of the people I asked in Bishkek had never been there, and those who had visited the site remembered it from a single trip long ago, perhaps with a school group. Our group encountered only two or three other people on the chilly morning we visited. The memorial’s visitors are mostly tourists to the area and relatives of the deceased. It appeared beautifully maintained, however, as well as beautifully designed. It is a powerful celebration of those who have died here at the hands of abusive power, and a glimpse into history both long-buried and fresh.

Central Asian Studies Program Travel

SRAS’ Central Asian Studies program offers a much more ambitious package that usually covers 3-4 other countries besides Kyrgyzstan. Students not on the Central Asian Studies program can often take some of these trips as optional add-ons.

Uzbekistan: Exploring the Ancient Cities

By Camryn Vaughn (Fall, 2019)

As part of the SRAS’ Central Asian Studies program, we spent about six days traveling Uzbekistan.

Read more about the history of Uzbekistan’s cities and how SRAS students travel through them on GeoHistory!

Originally scheduled as a two-week Central Asia tour, the London School in Bishkek and the tour company they booked our trip through had apparently both misunderstood Uzbekistan’s recently revised visa policies. Thus, we didn’t have the visas we needed and wound up heading back to Kyrgyzstan empty-handed. So, on our second try, we were looking forward to seeing the trip finally taken to completion.

The last week of November, we departed Bishkek at 11:30 am for a direct flight to Tashkent, landing at 11:50 am local time. Our guide, Donat (who invited us to call him Don, for short) met us at the airport upon our arrival and we began our city tour. It was miserably cold and wet. We had all checked the weather before we left, but our packing proved not necessarily reflective of exercising any forethought. Our shoes soaked and bodies frozen, we pressed on to Khast Imam Square to see the Barak Khan Madrassah, Kafal Shashi Mausoleum, and the Tillya Sheykh Mosque. Uzbekistan’s history is rich and steeped with stories of ruler Tamerlane and the Silk Road, and Don shared a wealth of information with us. Up next was the State Museum of Applied Arts. There, we learned about an important art form in Uzbek culture (and Uzbekistan’s number one most popular gift shop item!) called suzani. Part of a bride’s dowry, they are hand-embroidered textiles. The bride includes images on her suzani that symbolize wishes for her life and marriage, such as pomegranates for fertility or fish for a long life.

Our tour ended for the day and Don dropped the group off at a restaurant for a pre-arranged meal featuring local cuisine: shurpa soup, a tomato salad, and a meat and tomato dish. We were then transferred to the city’s train station for our four-hour ride to Bukhara. We arrived to Bukhara at 10:40 pm and met our driver and were delivered to our hotel.

The next morning we had our first day’s tour in Bukhara consisted of seeing the Lyabi Khauz complex which included the Kukeldash Madrasah, as well as the Poi-Kalyan Ensemble and the Kalyan Minaret, which is the symbol of the city. We then had free time until dinner. Our guide Lily, recommended a cafe at which we could try samsa, a popular Uzbek pastry stuffed with meat, potatoes, spinach, or pumpkin. After this, we walked around the town but it was so cold that we went back to the hotel to rest before dinner, which was pre-arranged at a restaurant near our hotel.

Lily met us the following day for a tour of Samanids Mausoleum, the Bolo Khauz Mosque, and the Fortress Ark. It was arranged that for 8 USD each, the group could participate in plov making for lunch. Unfortunately, this was an outdoor activity in an outdoor kitchen, but our hosts very kindly continued to pour us hot tea to keep us warm. While we waited for the plov to cook, our hosts showed us upstairs to the embroidery workshop. The master embroiderer demonstrated his craft and let us take some needle and thread for a spin! It turns out that we are better at making plov than we are at handcrafts.

Following lunch, we had free time until 2:30 pm the next day when it was arranged that the driver would take us to the train station. We slept in and spent the fourth day of our trip wandering the cold and snowy streets of Bukhara and ended up at an Italian restaurant for a last meal in the city before hopping onto the next train.

After an hour and a half staring at the stark countryside from a train window, we arrived in Samarkand at 5:30 pm. Guide-less until the next morning, some of the students arranged a taxi at the front desk and went out to Blues Cafe, a bar and grill we’d found online with good reviews that our taxi driver proved a little hesitant to drop us off at, seemingly due to its reputation among locals. It turned out to be a very smoky bar with underwhelming service and an interesting crowd. But the food was delicious!

The next day began our time in Samarkand. Our tour guide Sabir took us to the famed Registan Square with its surrounding madrassas and we sampled many dried fruits and sweets at Siab Bazaar. Following lunch at a cafe, we spent our free time walking to another bazaar to shop for souvenirs before we were driven to an arranged dinner at a local homestay where we were served a lot of delicious plov.

Day six began with Sabir showing us the mausoleum of the Prophet Daniel and how to drink three times from a nearby fountain of spring water, which was said to grant wishes. Next was the Ulug Beg Observatory, which also included a museum on-site that held artifacts from Ulug Beg’s astronomical studies and his immense contributions to the understanding of the cosmos. Following the observatory, we visited the Hojom silk carpet factory where we were given a tour and saw carpet-weaving in action. No wonder hand-made carpets are so expensive; it is intricate and difficult work. After touring the factory (and its gift shop), we dined once more on plov, Uzbekistan’s proud national dish. Following lunch, our guide showed us the Gur-Emir Mausoleum, where Tamerlane is buried. This wrapped up our time in Samarkand.

We then boarded a train at 5:30 pm and arrived back in Tashkent at 8:00 pm. A driver delivered us to our hotel and we woke up the next morning to meet our guide Don once again to see more of the capital. He took us to Independence Square and one of the capital city’s main streets, Broadway. We then visited Usto-Shogird ceramic studio and learned about the different design styles of Uzbekistan pottery. After lunch, the group was returned to the hotel with plans to meet Don later for dinner and drinks. He recommended Steam Bar, a must-see place if you’re in Tashkent. There was live music and tasty burgers in a space decked-out in steam punk aesthetic. We enjoyed learning more about our guide’s experience living in Uzbekistan and chatting with more locals on our last night.

The following morning, we were dropped off at the airport early for our 7:50 am flight. We arrived to Bishkek at 10:00 am local time and were met by the London School coordinator, who took us back to London School via taxis.

In contrast to our Turkmenistan trip, there was a lot of free time after tours and fewer meals included in Uzbekistan. This was something of a problem as spending money was difficult sometimes. Cards aren’t commonly accepted in restaurants, and are naturally not accepted at bazaars or many souvenir-selling locations. The Uzbek currency is rather inflated as well; the exchange rate is 0.00010 som to 1 USD. However, things are fairly inexpensive and the large spills spit out by ATMs are too big for businesses to make change for. Despite this and the cold, the students really enjoyed our week in Uzbekistan and learned a lot about the country’s history and modern culture.

Turkmenistan: A Wild and Facinating Tour

By Camryn Vaughn (Fall, 2019)

SRAS students in Bishkek on the Central Asian Studies program spent four days in Turkmenistan. We were so excited about this unique and rare opportunity to visit the country. Visas can be difficult to get and the country is less visited than even North Korea. We had spent a lot of time in the Central Asian Studies program learning about the politics, economics, and culture of Turkmenistan. The country is technically rich, thanks to all its oil and natural gas reserves. However, it has struggled, due in large part to its political economy, to develop and even provide basic goods to its population.

Further, Human Rights Watch lists Turkmenistan as one of the world’s most repressive countries; two cults of personalities have been running the scene since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The country was first ruled by President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov (better known as “Turkmenbashi,” a title he took that means “Father of the Turkmen People”). After Niyazov’s death in 2006, current President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov took over. As nervous as we were about going to such a controlled country, we were eager to experience the culture firsthand.

Getting there was fairly tiring; our flight left Almaty in Kazakhstan at 2:00 am and we arrived at Ashgabat in Turkmenistan at 3:00 am. We had been given little information regarding customs and, after wandering around, we ended up at the end of the very long visa line. Per program instructions, we had USD with which to pay. The process was long, and it wasn’t until 4:00 am that we had found our luggage and our guide, Maysa, who introduced herself and shepherded us onto a bus to take us to the hotel. We were all pretty groggy and had until 11:00 am that morning before departing on our tour. The five-star hotel was extremely comfortable and we slept soundly.

Day 1: White Marble and the Gates of Hell

To begin the day, we were given a tour of the capital city, Ashgabat. It is famously known as the City of White Marble, which became clear in the daylight. President Berdimuhamedow has a few interesting quirks, one of them is his obsession with collecting Guinness World Records. Ashgabat has the world’s highest density of white marble structures. There are 543 white marble buildings that cover a total of 4.5 million square meters.

We visited Independence Park, the Neutrality Arch, and the Ruhnama Book Monument. Many government buildings, such as the center for media shaped like a book and the Ministry of Horses, were pointed out to us from the bus as we drove around the city. We had heard that as a capital city, Ashgabat would feel eerily empty. In the new part of Ashgabat, it certainly felt that way. These tourist sites we visited were the opposite of crowded; we were often the only people there aside from the workers cleaning and maintaining the grounds.

After an informative visit to the National Museum, we had lunch at a small local cafe where it was decided to add an additional excursion to our program. A visit to the famous Darvaza Gas Crater, known also as the “Gates of Hell” wasn’t included in our itinerary, but our guide informed us that if we were each interested in paying 55 USD for the three-hour drive there and back that night, we could modify the next day. We jumped on the opportunity, and that afternoon we met our three drivers and climbed into their SUVs.

With three of us to each car, I rode with another student and Maysa. We tried to use the opportunity to speak with her about her experience as a Turkmen citizen, aware that she would likely be hesitant to reveal her genuine opinion. This prediction was manifested when Maysa told us nicely that we shouldn’t believe everything we’ve seen on the Internet. Our conversation was interrupted as she pointed out a camel caravan meandering through the desert, the first of many we would see on our drives through the country.

The sun set and under dusty purple skies, we turned onto an unmarked road after driving straight for two and a half hours. In the growing darkness, we eventually began to see a faint glow grow brighter and brighter – we had reached our destination! The Darvaza Gas Crater is a result of a mining accident at a natural gas deposit. Soviet geologists began drilling at the site in 1971, and after some equipment fell into the 20-meter wide cavern, it was set on fire in an attempt to burn off the gas out of fear that the gas emitting from the hole was toxic. The flames have yet to go out.

After hanging out for about an hour, we began the journey home. We arrived at the hotel at midnight and after a good night’s sleep, were ready to roll onward the next morning.

Day 2: Ancient Ruins and Goddesses

We started our day at the Gulistan Bazaar, Ashgabat’s Russian bazaar. It was a good place to pick up little souvenirs. Then we headed to Nisa, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, about 20 kilometers from the capital. Located there are the remains the Parthian capital. From Nisa, we drove into the Kopetdag Mountains on the border of Iran for a visit to the Nohur village.

For me, this was the most fascinating part of my time in Turkmenistan. We first arrived to have lunch with a host family. Once we were seated on rugs and carpets and served food, Maysa informed us that the villagers claim that they’re descendants of Alexander the Great. The Nohurli tribe’s isolation has led to the development of an indiscernible Turkmen dialect and the continued practice of very traditional customs, such as polygamy. Maysa turned to us girls and let us know to not be alarmed if someone tried to approach her to offer camels in exchange for us to be their wives. Over some delicious lagman stew, we immediately began calculating how many camels we thought we might be worth. Turns out, the wives are expected to pay back the worth of the camels in housework, so the fewer camels your family is given in exchange for you, the less housework you have to do. Much to our disappointment, no camel bartering took place. (I’m sure the local men took one look at me and knew I couldn’t darn a sock to save my life.)

Having expressed our thanks to our hosts, we passed by the gnarliest scene I have ever laid eyes on: a huge cemetery with a mountain goat skull protruding from the top of each grave. Mountain goats are considered sacred; their horns are said to ward off evil spirits. After passing the cemetery, we arrived at a pilgrimage site called Kyz Bibi, named after a female deity who is known to grant wishes of women. At the site is a small hole in the mountainside, said to be where Kyz Bibi was hidden to avoid an unwanted marriage.

Next on the agenda that day was a dip in Kow Ata lake. This lake is special in several ways: it is located 60 meters underground in a cave, the warm sulfuric waters are said to be healing, and it is home to Central Asia’s largest bat colony! Several of us brought our swimsuits and spent about an hour swimming around in the freakishly dark and deep lake.

On our way back to Ashgabat that evening, we stopped at the Turkmenbashi Mosque and Mausoleum, the largest mosque in Central Asia and the main mosque of Turkmenistan. Interestingly, we noticed that along with the traditional Islamic verses from the Koran, text in Turkmen decorates the interior which is fairly sacrilegious. The text is from the first president’s book on spirituality and morality and is named for him. He is commonly referred to as Turkmenbashi, or “Father of the Turks”.

That night at dinner, we bonded with Maysa while the venue entertainer serenaded us on the clarinet on stage behind us. Maysa had studied abroad in Europe and expressed her happiness about having her first young tour group – usually, she’s wrangling older folks, but she told us we made her feel like she was a student again.

We had great conversations with Maysa about cultural differences, especially dating and marriage. In Turkmenistan, it’s very common that once you get to be around 25 and you’re still without a partner, your family finds someone for you. After a few chaperoned dates and usually one or two months, you get hitched. She explained it with a heart-wrenching phrase: “We let the love come after marriage.” We left the restaurant thankful that we weren’t active in the Turkmen dating scene and were on our way to go around the world’s largest indoor ferris wheel once. There was nothing particularly spectacular about this, aside from its position as a Guinness World Record.

Day 3: Merv, Manti, and Camel Milk

The next morning, we began our day with a drive to Mary, a four-hour journey. We stopped part way through to walk around the Anau Mosque ruins and the Abiverd Silk Road town remains. Just past Mary is a town called Merv, where we had a very interesting lunch. We dined on manti, which are delicious Central Asian dumplings. Maysa also ordered camel milk for us to try. It was bitter, but not as bad as we had expected. We walked around a dilapidated Russian Orthodox cemetery next to the restaurant while our driver did his daily prayers.

Ancient Merv is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, famous for its role as one of the largest Central Asian cities on the Silk Road. We spent the afternoon traveling between the different monuments and ruins. Back in Mary that evening, we visited a Russian Orthodox church and then had dinner at a practically empty restaurant (save from the waitstaff and the venue performer singing covers of pop songs) that also had a dance floor.

Day 4: On To New Adventures

The next morning, we had a three-hour drive to Turkmenabad located on the border of Uzbekistan, which would be next our journey through Central Asia. We had lunch at a café nearby and were dreading saying goodbye to Maysa. She accompanied us as far as she could through customs as we exited Turkmenistan and there was a round of hugs and promises to keep in touch.

The trip was organized by the London School and the tour company Kyrgyz Concept. Accommodation in five-star hotels, ground transportation, English-speaking guide, flights, and meals were all included as part of our program. The meals were especially nice: each included a salad, soup, entrée, dessert, and drink.

The trip to Turkmenistan is easily the wildest, most unique experience I’ve had traveling. I wouldn’t want it to have happened any other way, and the other students agree. Maysa was a fundamental part of how much we enjoyed our time there, and I’m so grateful that she shared her country with us so candidly.

Kazakhstan: All in a Weekend

By Mikaela Peters (Fall, 2019)

Almaty, Kazakhstan is just a four-hour drive from Bishkek, where SRAS’s Central Asian Studies program is based. We arrived midday on a Saturday and departed late at night the next day. Yet the amount of time spent in Almaty was jam-packed with cultural experiences.

Upon arrival to Almaty, we ate at a local café that offered a wide range of options, including both local Kazakh dishes, such as lagman, but also western dishes, including anything from salads to pasta. This café was an approximately five-minute walk from Panfilov Park, located right near a KFC and Hardee’s, showing immediately the international side of Kazakhstan.

Panfilov Park functioned as our meeting place throughout much of the trip’s duration. We parked our marshrutka (van) there and proceeded straight to the famous Zeleniy Bazar (Green Bazaar). We exchanged money quickly before proceeding to the bazaar, in case we wanted to purchase any souvenirs. When we first arrived at the bazar, we were all very impressed by how much more organized this bazar was than the ones in Bishkek. It seemed like there was a designated section for each type of product, from clothes to food to souvenirs. We had ten minutes to explore here before meeting our SRAS guide back at our designated meeting spot. I personally took advantage of this time to buy souvenirs.

After this, we headed back to the park and saw some of the attractions there starting with the colorful Zenkov’s Cathedral. Inside, we women were provided with scarves to respectfully cover our heads. We then walked by the World War II memorial, which had been made during the time of the Soviet Union. It has an eternal flame to honor the men who lost their lives in the war. It is a large monument, and quite distinct. Its main attraction is a sculpture of a soldier’s head protruding out of a wall of what appears to be black granite.

Right near this monument is the Musical Instrument Museum, which I had also wanted to visit in my previous time here, but had been closed. We had a Russian speaking guide and began by going through all of the historical instruments, gradually giving way to more modern instruments. These included drums, wind instruments, and many different stringed instruments. This museum was established in 1980 and includes instruments from all regions of the world, from many different countries, including Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, France, Moldova, Lithuania, Estonia, Armenia, Georgia, Russia, Ukraine, Korea, Japan, Morocco, and more. This museum was allegedly built during Kazakhstan’s Soviet “golden years,” which took place in the 1980s and during which there was a lot of development taking place in Kazakhstan.

At this museum, we briefly ran into some Americans on a tour of Central Asia, just like us. They had already been to Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and were keen on sharing their impressions. Bishkek was to be their final stop.

Before heading back to the hostel, our local guide was kind enough to take us to Starbucks, which we had all been raving about since we got to Almaty. This was a very fulfilling experience for many of us since it had been months since we’d had our favorite, familiar drinks. It was at Starbucks that we encountered another American who happened to frequent the city every so often. At a glance, Almaty appeared more expat-friendly than Bishkek, with more western establishments, including McDonalds, Starbucks, and many more. Almaty actually reminded us all somewhat of America. The roads were generally free of potholes and the government had done a good job of nearly eradicating marshrutkas and exclusively replacing them with buses. In Bishkek it is nearly the other way around. All of these modern amenities that Almaty appeared to have made us, for a moment, wishful that we were studying here instead. But we got over it, and instead just vowed to come back one weekend.

After our Starbucks fix, we checked into our hostel. After getting settled, we walked to Burger King for dinner, which proved to be an interesting cultural experience since you can order a wrap resembling schwarma, which actually ended up being my meal of choice. It tasted good for a Burger King item in my opinion.

After that, we went back to the hostel and were given designated free time. I ended up using this time to check out a local café in one of the new shopping centers, Dostyk Plaza, along with another student. After enjoying a chocolate soufflé, we walked down to a building that was both a mosque and a kid’s school. There wasn’t much to see at night. We proceeded back to the hostel.

The next morning, we had breakfast at the hotel before setting out for our first stop, Almaty’s History Museum, which was the only museum we’ve ever gone to where we didn’t have a guide. This was somewhat fortunate in that I felt that I had more time to explore the museum in depth. It had three floors and included animal artifacts at the first level, artifacts from village folk on the second level, and on the third level there was both modern art and a testament to all of Kazakhstan’s recent national accomplishments within the past thirty years or so, particularly during the rule of Nursultan Nazarbayev.

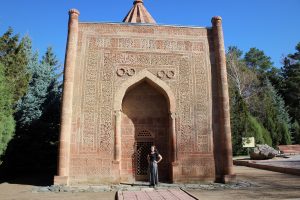

After the museum we walked through the Republic Square Park to the presidential monument of Nursultan Nazarbayev. There is a book at the bottom of it where you can put your handprint inside of his.

After going back to the museum to our marshrutka and driving back to our Panfilov Park parking spot, we were given thirty minutes of free time. Half of the students went to Starbucks for another Starbucks fix, while the other half of us walked around the park and encountered an older man with a kind face and a handle bar mustache on the street playing the accordion. We gave him some money and ended up talking to him for quite a bit. He was very talented and could play anything from old Soviet music to the Beatles to the Pirates of the Caribbean soundtrack to Desposito. He explained how he had adjusted his strategy to playing popular international songs to appeal to the many foreigners he encountered. He explained to us that conversely, he was impressed that we had learned Russian. He said that playing music was easy, but that learning another language was hard.

Reconvening with the other students, we had lunch at the same café as the day before. Not everyone was so thrilled about this, but I personally didn’t care because I at least knew what to order.

After lunch, we drove to Shymbulak and rode its cable car, which is used as a gondola for their ski resort during the ski season, which begins in November. The cable car goes up three levels, but today, only the part up to the first level was working. When we reached that area, it was small. We had an hour and a half there, in which we hung out, walked around, and got warm drinks. Here I was able to find out more about their ski resort, such as costs, and when it opens, in case I wanted to come back, since Almaty is pretty close to Bishkek. I learned that one ticket is 9000 tenge per day, or about $23. There was also a gift shop, which although overpriced, had some nice items, including mugs, t-shirts, hats, and sunglasses.

On our way up on the cable car, we noted an outdoor ice-skating rink a little bit further down from where we got off at our stop. This ice-skating rink holds the record as the world’s highest ice-skating rink in altitude. On the way down, we partially regretted not trying to go skate.

Following this excursion was our final activity of the evening – eating dinner at a homestay with a local Kazakh family. We arrived a little early, and were corralled out of the way and into the living room for some friendly conversation until dinner was ready. Dinner with this homestay ended up being very fun because the daughter and the son of the family were around our age. The son was a great conversationalist and asked us a ton of questions and also gave us a lot of information about himself and Kazakh culture at large. While the daughter was much quieter and more reserved, I connected with her at the dinner table and was able to get her contact information for the future when I plan to come back to Almaty.

Our dinner was delicious and consisted of beshbarmak, a dish considered to be traditional to both Kyrgyz and Kazakh cultures (which are quite close). We also had a few other salads, such as a beet salad and an assorted vegetable salad, and many candies and sweets for dessert.

Following our meal, we went to the airport for the next leg of our journey – which would take us to Turkmenistan.

This had to have been the longest days of the trip, ending with a 2 AM flight to Ashgabat, the city of White Marble, which we were all looking forward to a great deal. The flight was just under three hours, which didn’t leave too much time to catch up on sleep.

Despite how excited we were for our upcoming journey to Ashgabat, we also yearned for more time in Almaty. Fortunately, another quick trip to Almaty in the future can easily be made a reality any upcoming weekend with the help of a short, intercity marshrutka ride.